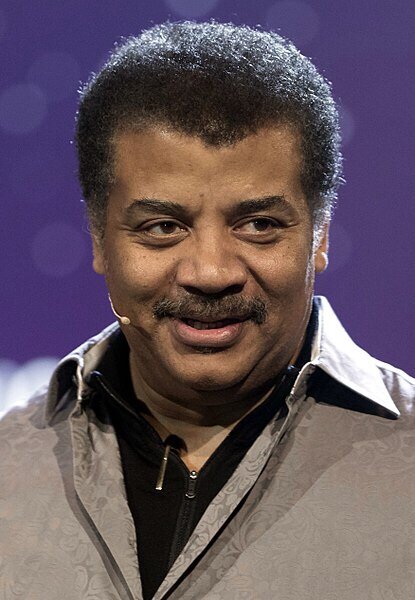

Neil deGrasse Tyson's Tweet Was Terrible. His Apology May Have Been Even Worse.

A few months ago, Astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson made a big mistake. He followed it up with a bigger one.

America was reeling after at least 31 people were killed in back-to-back mass shootings--the first in El Paso, Texas on Saturday morning, and then in Dayton, Ohio only 13 hours later.

That Sunday, Tyson tweeted the following:

In the past 48hrs, the USA horrifically lost 34 people to mass shootings.

— Neil deGrasse Tyson (@neiltyson) August 4, 2019

On average, across any 48hrs, we also lose…

500 to Medical errors

300 to the Flu

250 to Suicide

200 to Car Accidents

40 to Homicide via Handgun

Often our emotions respond more to spectacle than to data.

In the past 48hrs, the USA horrifically lost 34 people to mass shootings.

On average, across any 48hrs, we also lose...

500 to Medical errors

300 to the Flu

250 to Suicide

200 to Car Accidents

40 to Homicide via HandgunOften our emotions respond more to spectacle than to data.

While Tyson's quote seems to be scientifically accurate, many criticized it as being unfeeling and cold-hearted.

Then, that Monday, Tyson took to Facebook to apologize...kind of.

"My intent was to offer objectively true information that might help shape conversations and reactions to preventable ways we die," wrote Tyson. "Where I miscalculated was that I genuinely believed the Tweet would be helpful to anyone trying to save lives in America. What I learned from the range of reactions is that for many people, some information--my Tweet in particular--can be true but unhelpful, especially at a time when many people are either still in shock, or trying to heal--or both."

I applaud Tyson for this initial reaction, and for learning a valuable lesson. At this point, he could have simply said sorry to the people he hurt.

Instead, he said this:

"So if you are one of those people, I apologize for not knowing in advance what effect my Tweet could have on you."

Ooh. Not good.

Both the initial tweet and the quasi-apology are perfect examples of how our words can unintentionally cause harm, even when we're trying to help.

I'd argue that applying emotional intelligence, the ability to understand and manage emotions effectively, could have greatly helped Tyson in this instance.

There are two main reasons why the famous scientist's initial tweet and subsequent Facebook post sparked outrage:

1. It lacked empathy.

Tyson argues that he was attempting to use data to "help shape conversations and reactions to preventable ways we die."

That may be true, but the way he approached the subject severely lacked empathy. It showed a lack of feeling for the persons who just lost loved ones. It also equated many forms of accidental death to a deliberate act of mass murder.

Further, the timing of Tyson's tweet--just a couple of days after the shootings, could be equated to rubbing salt in a fresh wound.

2. It lacked respect.

As mentioned, much of Tyson's follow up Facebook post was good. It showed evidence of learning from the criticism of others, which is an invaluable skill of emotional intelligence.

But the apology fell flat.

When Tyson says "if you are one of those people, I apologize for not knowing in advance what effect my Tweet could have on you," many people hear:

"I'm sorry I couldn't tell the future. And that I couldn't foresee that a few oversensitive people wouldn't be able to handle the truth."

Of course, I'm not implying this is the tone Tyson was attempting to strike--only pointing out that the subsequent response shows that's how people felt. (I've reached out to Mr. Tyson for comment and will update this story if I receive one.)

Neither is my goal to criticize Mr. Tyson as a person. We all make gaffes from time to time; the only difference with celebrities is that their mistakes are analyzed to a much greater degree.

But by taking a closer look at this situation, we can all learn from it.

The next time tragedy strikes, or the next time you see others in an emotional state, don't think about how you can use this to further an agenda, or how you can convince someone of points you feel strongly about.

Instead, focus on showing empathy and fellow feeling.

Focus on listening and understanding, instead of speaking.

And when it does come time to speak, try to comfort.

Or at least, to relate.

If you succeed, you'll be helping, instead of hurting.

And we could all use a little more of that in this world.

Enjoy this post? Check out my book, EQ Applied, which uses fascinating research and compelling stories to illustrate what emotional intelligence looks like in everyday life.

A version of this article originally appeared on Inc.com.